.

.

.

I published an earlier version of this story on July 29, just as the party conventions closed. A friend of mine soon afterwards published a (better-written, I’m sure) analysis in the Washington Monthly pointing people towards the same electoral map. With the polls in the Presidential race recently tightening so much, this seems like a good moment to take a look at it again.

The bottom line is that we really could be looking at an Electoral College tie (or other failure of any candidate to get a majority) this year. And if that happens, any candidate — Paul Ryan, Mike Pence, Newt Gingrich, Gary Johnson — who gets even just one electoral vote, or whatever other number is required to put them into third place — could become President. All they would need is to get a majority of the votes of the 50 state delegations in the House of Representatives. (These delegations lean massively Republican, so don’t delude yourself that either Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton would have a chance.) The resulting free-for-all — with Big Money interests trying to coerce delegates to vote for a third alternative to Donald and Hillary and for thenfor representatives to do the same — would make the 2000 race look like a nursery school game of tag by comparison.

Here’s the original story, somewhat edited and then updated:

It’s long been understood that the Electoral College vote could end up without any candidate having a majority of the 538 votes, and people have written about that. Sometimes this is called an “electoral college tie” — but that’s not strictly true. All that’s necessary is for no one to reach 270 votes out of the 538. This could happen because of a 269-269 tie — or it could happen because a third candidate picks up enough electoral voters to block either of the other candidates from a majority (as would be the case if Gary Johnson took Maine and left a 269-265, 268-266, or 267-267 split between Trump and Clinton), or it happen due to a “faithless elector.”

Yes, if either Trump or Clinton won 270-268 — it would be possible for a single elector in that majority to — breaking the law, perhaps, but nevertheless — cast their vote for a third party ticket, or even for Michelle Obama or Gary Johnson. And then — if Congress or the courts didn’t find a way to squash it — that person would become just as eligible to be selected by the House of Representatives, with each state delegation getting one vote (so that Wyoming gets the same amount of votes as California and a tied state delegation gets no vote at all) as the two major party candidates who had almost but not quite 270. (Their running mate could not be selected; the Senate chooses between only the top two vote-getters as Vice-President. Joe Biden would still be able to cast the tie-breaking vote.) Note that the story linked to up above is incorrect: it doesn’t matter whether the House of Representatives goes overwhelmingly Democratic this year or not, so long as the Republicans hold either a majority of 26 state delegations — or perhaps even simply a majority of those able to cast a vote (i.e., not tied or entirely vacant.) Congress itself would have to decide on which rule to apply.

This is a perennial (well. perennially a quadrennial) story; I even wrote about it here myself at the beginning of July to explain why Bernie wouldn’t run as a third party candidate. (Essentially, it would guarantee a Trump victory if he did well enough to hold both candidates below 270 electoral votes. Remember, if this happens, the next President is definitely a Republican or a Libertarian.) And in those stories, writers often come up with plausible-seeming scenarios where, if the chips fell just right, we could get an electoral vote tie.

Well, guess what? Or, don’t guess: just look at the following map, adapted from the predictions at Nate Silver’s fivethirtyeight.com.

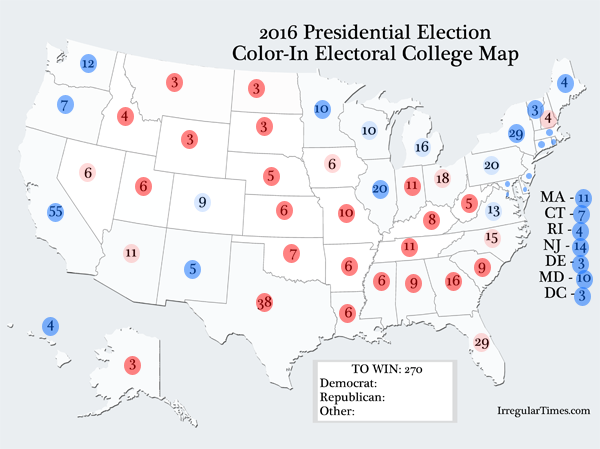

The direction in which each state leaned as of the closing day of the 2016 Democratic convention. Light pink and blue indicate likely swing states.

Each state’s number of electoral votes is highlighted. The bright blue states are considered safe for Clinton; the bright reddish ones are considered safe for Trump. (I don’t actually believe that Minnesota, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, Oregon or Maine — at least it’s second district, which gets its own single electoral vote — are truly “safe” for Clinton, and I’m not sure what if anything is actually “safe” for Trump, who could crash through a guard rail at any time. But his “safe states” currently do seem safer than the others.) The light blue states (Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Colorado) are “Clinton-held” swing states; the pink states (Nevada, Arizona, Iowa, Ohio, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Florida) are “Trump-held” swing states.

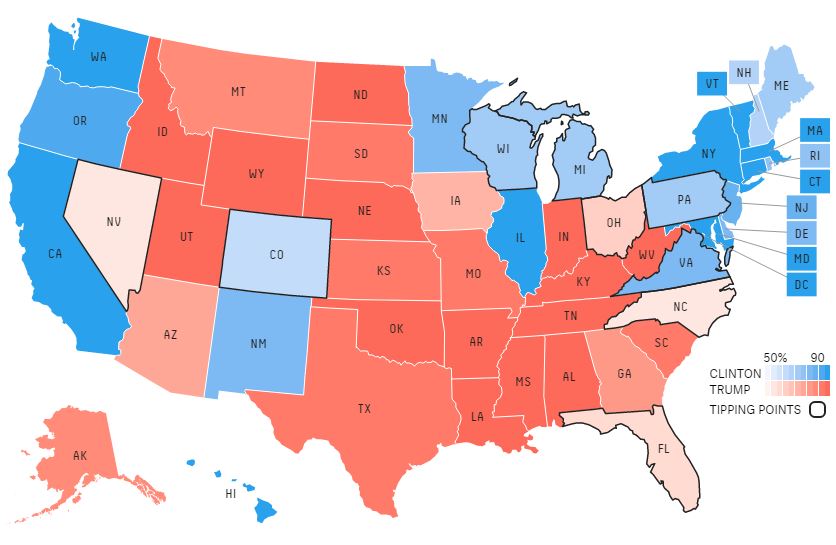

These projections are taken from Nate Silver’s site as of yesterday. At that point, every state was leaning in the same direction in each of the three ways that Silver calculates his predictions. These three ways are: (1) the “now-cast” of where the vote would be expected to go if the election were held today; (2) the “polls-only” model, which simply aggregates the polls for each state; and (3) the “polls-plus” model, which takes into account not only polls but the state of the economy, presidential popularity, and perhaps a little more. Trump does best in the “now-cast” (#1) and Clinton best in the “polls plus” model (#3), with Clinton prevailing in the “polls only” model (#2). But the states fundamental direction stays the same in each model: it’s just that in the “now-cast” Clinton safe states turn into swing states and the swing states get even more swingy, and in the “polls-plus” safe Trump states become swingy and his swing-states get closer to flipping. (In today’s “polls-plus” model, for example, Nevada, Iowa, and New Hampshire switched from pink to blue. Don’t get used to it; the latter two margins are each half a percent.)

So what’s so interesting? Well, if things were stay the same as on July 28 within a fairly broad range of conditions — which probably won’t happen, but it was the best estimate for each state as of that date, and it’s still true for models #1 and #2 — then this is what the final map would look like. Add up all of the electoral votes of the red and pink states. And then add up all of the electoral votes for the blue and light-blue states.

They both add up to 269. As of July 28, the best estimate on a state by state basis, not including the correlations of effects in the various races that turn the path of the election, is an Electoral Vote tie.

Back to September 18. How do things look now? Well, they look somewhat familiar:

Let’s do Trump’s “pink states” first: Nevada, a faint check! Arizona, check! Iowa, red check! Ohio, check! North Carolina, check! Florida, check! New Hampshire — not check! — but not by a safe margin.

Now let’s do Hillary’s “light blue” states: Colorado: a faint check! Wisconsin, check! Michigan, check! Pennsylvania, check! Virginia, check! But look at that softening in Maine — which apportions one delegate for each Congressional district as well as two to the statewide winner! And Rhode Island and Delaware join the “could become a real swing state” group, along with Oregon, Minnesota, and New Mexico.

All those votes in the South that secured Hillary the nomination will have bought her … nothing. The northeast and norther tier of the industrial midwest, where Sanders did well? They could easily tip the election to Trump.

One of my arguments recently among Democrats and other lefties has been that people should stop arguing over whether they will vote for Hillary or for Jill Stein! Everyone should just do what they want: California is going blue either way (unless Stein and Trump both get so far up in the polls that even I feel the need to vote for Hillary just in case — which I would — and if for some reason Hillary lost California there’s no plausible way that that could make the difference in the result, which would already be a Reaganesque slaughter.

If you’re a Hillary partisan who thinks that a Trump victory would destroy civilization, then get the hell out to Nevada and walk precincts for her there, like I did for Obama in 2008. If you can establish residency there in time to vote — the deadline is October 8, and you have to establish a residence there (could be a temporary rental), stay there through election day, and give up your claim to California residence, although you can recapture it later if you like paying state income taxes — then so much the better! (Their U.S. Senate candidate needs you, too!)

If you are a “HILLARY BEATING TRUMP IS EVERYTHING” Democrat, but you don’t focus on Nevada even if it looks like it could determine the Presidency, then stop complaining about people voting for Stein or staying home — because your vote for Hillary in California (or your squeezing out more votes for Hillary in Nevada by browbeating millennials and other Sandersnistas, or whatever you are pleased to imagine is productive) simply will not matter. If the national election is close, though, then Nevada will!

(I know that Republicans are reading this as well and wondering if they should relocate — well, that’s publication for you! Everyone can see it! Doesn’t that give Democrats reading this more motivation, though?)

Arguments among Californians about our Presidential voting preferences are wasting everyone’s time — and if that’s what you’re doing right now it shows that you don’t really care that much about the result. If you claim to be all about the Presidential race to the expense of everything else — then right now you are on the wrong side of the mountains!

California has enacted the National Popular Vote bill. When it goes into effect it will guarantee the majority of Electoral College votes and the presidency to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in the country.

Every vote, everywhere, for every candidate, would be politically relevant and equal in every presidential election.

No more distorting and divisive red and blue state maps of pre-determined outcomes.

No more handful of ‘battleground’ states (where the two major political parties happen to have similar levels of support among voters) where voters and policies are more important than those of the voters in 38+ predictable states, like California, that have just been ‘spectators’ and ignored after the conventions.

The bill would take effect when enacted by states with a majority of the electoral votes—270 of 538. All of the presidential electors from the enacting states will be supporters of the presidential candidate receiving the most popular votes in all 50 states (and DC)—thereby guaranteeing that candidate with an Electoral College majority.

The bill has passed 34 state legislative chambers in 23 rural, small, medium, large, red, blue, and purple states with 261 electoral votes. The bill has been enacted by 11 small, medium, and large jurisdictions with 165 electoral votes – 61% of the 270 necessary to go into effect.

National Popular Vote

This is a pretty shitty erosion of state sovereignty achieved by exploiting state sovereignty.

At a minimum, I appreciate the ridiculousness.

There would be no erosion of state sovereignty.

States have the responsibility and exclusive constitutional power to make their voters relevant in every presidential election. Now, voters in 38 states are politically irrelevant.

States are choosing to change their state winner-take-all laws (not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, but later enacted by 48 states), without changing anything in the Constitution, using the built-in method that the Constitution provides for states to make changes.

The National Popular Vote bill would replace state winner-take-all laws that award all of a state’s electoral votes to the candidate who get the most popular votes in each separate state (not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, but later enacted by 48 states), in the enacting states, to a system guaranteeing the majority of Electoral College votes for, and the Presidency to, the candidate getting the most popular votes in the entire United States.

The bill retains the constitutionally mandated Electoral College and state control of elections, and uses the built-in method that the Constitution provides for states to make changes. It ensures that every voter is equal, every voter will matter, in every state, in every presidential election, and the candidate with the most votes wins, as in virtually every other election in the country.

Under National Popular Vote, every voter, everywhere, would be politically relevant and equal in every presidential election. Every vote would matter in the state counts and national count.

Candidates would need to care about voters across the nation, not just undecided voters in the current handful of swing states.

The National Popular Vote bill concerns how votes are tallied, not how much power state governments possess relative to the national government. The powers of state governments are neither increased nor decreased based on whether presidential electors are selected along the state boundary lines, or national lines (as with the National Popular Vote).

Sorry, but so long as the problem of Faithless Electors remains — and it could be exacerbated under this system — I don’t trust it. Imagine if Hillary won and among the signatories were Alabama, Oklahoma, West Virginia, Wyoming, and Utah. We’re counting on their electors to vote against their own states’ interests, when their own states have the prerogative to punish them — or not? No thanks. There’s no safe shortcut to a Constitutional Amendment eliminating the Electoral College.

That’s not the problem.

The problem is repealing or amending the 12 Amendment requires a majority of legislators and a super majority of states to achieve. This “compact” bastardizes the Constitution by allowing short circuit of that requirement. Sovereignty for big blue states, but not for the wee red ones.

Put another way, this is mob rule, which (ironically), the college was supposed to protect us against.

There is no problem of Faithless Electors.

Now 48 states have winner-take-all state laws for awarding electoral votes, 2 have district winner laws. Neither method is mentioned in the U.S. Constitution.

The electors are and will be dedicated party activist supporters of the winning party’s candidate who meet briefly in mid-December to cast their totally predictable rubberstamped votes in accordance with their pre-announced pledges.

The current system does not provide some kind of check on the “mobs.” There have been 22,991 electoral votes cast since presidential elections became competitive (in 1796), and only 17 have been cast in a deviant way, for someone other than the candidate nominated by the elector’s own political party (one clear faithless elector, 15 grand-standing votes, and one accidental vote). 1796 remains the only instance when the elector might have thought, at the time he voted, that his vote might affect the national outcome.

States have enacted and can enact laws that guarantee the votes of their presidential electors

The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld state laws guaranteeing faithful voting by presidential electors (because the states have plenary power over presidential electors).

The National Popular Vote bill says: “Any member state may withdraw from this agreement, except that a withdrawal occurring six months or less before the end of a President’s term shall not become effective until a President or Vice President shall have been qualified to serve the next term.”

This six-month “blackout” period includes six important events relating to presidential elections, namely the

● national nominating conventions,

● fall general election campaign period,

● Election Day on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November,

● meeting of the Electoral College on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December,

● counting of the electoral votes by Congress on January 6, and

● scheduled inauguration of the President and Vice President for the new term on January 20.

Any attempt by a state to pull out of the compact in violation of its terms would violate the Impairments Clause of the U.S. Constitution and would be void. Such an attempt would also violate existing federal law. Compliance would be enforced by Federal court action

The National Popular Vote compact is, first of all, a state law. It is a state law that would govern the manner of choosing presidential electors. A Secretary of State may not ignore or override the National Popular Vote law any more than he or she may ignore or override the winner-take-all method that is currently the law in 48 states.

There has never been a court decision allowing a state to withdraw from an interstate compact without following the procedure for withdrawal specified by the compact. Indeed, courts have consistently rebuffed the occasional (sometimes creative) attempts by states to evade their obligations under interstate compacts.

In 1976, the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland stated in Hellmuth and Associates v. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority:

“When enacted, a compact constitutes not only law, but a contract which may not be amended, modified, or otherwise altered without the consent of all parties.”

In 1999, the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania stated in Aveline v. Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole:

“A compact takes precedence over the subsequent statutes of signatory states and, as such, a state may not unilaterally nullify, revoke, or amend one of its compacts if the compact does not so provide.”

In 1952, the U.S. Supreme Court very succinctly addressed the issue in Petty v. Tennessee-Missouri Bridge Commission:

“A compact is, after all, a contract.”

The important point is that an interstate compact is not a mere “handshake” agreement. If a state wants to rely on the goodwill and graciousness of other states to follow certain policies, it can simply enact its own state law and hope that other states decide to act in an identical manner. If a state wants a legally binding and enforceable mechanism by which it agrees to undertake certain specified actions only if other states agree to take other specified actions, it enters into an interstate compact.

Interstate compacts are supported by over two centuries of settled law guaranteeing enforceability. Interstate compacts exist because the states are sovereign. If there were no Compacts Clause in the U.S. Constitution, a state would have no way to enter into a legally binding contract with another state. The Compacts Clause, supported by the Impairments Clause, provides a way for a state to enter into a contract with other states and be assured of the enforceability of the obligations undertaken by its sister states. The enforceability of interstate compacts under the Impairments Clause is precisely the reason why sovereign states enter into interstate compacts. Without the Compacts Clause and the Impairments Clause, any contractual agreement among the states would be, in fact, no more than a handshake.

The U.S. Constitution says “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors . . .” The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly characterized the authority of the state legislatures over the manner of awarding their electoral votes as “plenary” and “exclusive.”

The normal way of changing the method of electing the President is not a federal constitutional amendment, but changes in state law.

Historically, major changes in the method of electing the President have come about by state legislative action. For example, the people had no vote for President in most states in the nation’s first election in 1789. However, now, as a result of changes in the state laws governing the appointment of presidential electors, the people have the right to vote for presidential electors in 100% of the states.

In 1789, only 3 states used the winner-take-all method (awarding all of a state’s electoral vote to the candidate who gets the most votes in the state). However, as a result of changes in state laws, the winner-take-all method is now currently used by 48 of the 50 states.

In 1789, it was necessary to own a substantial amount of property in order to vote; however, as a result of changes in state laws, there are now no property requirements for voting in any state.

In other words, neither of the two most important features of the current system of electing the President (namely, that the voters may vote and the winner-take-all method) are in the U.S. Constitution. Neither was the choice of the Founders when they went back to their states to organize the nation’s first presidential election.

The normal process of effecting change in the method of electing the President is specified in the U.S. Constitution, namely action by the state legislatures. This is how the current system was created, and this is the built-in method that the Constitution provides for making changes. The abnormal process is to go outside the Constitution, and amend it.

The National Popular Vote bill does not require repealing or amending the 12 Amendment.

There is nothing in the U.S. Constitution that needs to be changed in order to have a national popular vote for President. Awarding all of a state’s electoral votes to the candidate who gets the most votes inside the state is not in the U.S. Constitution. It is strictly a matter of state law.

Interstate compacts are supported by over two centuries of settled law guaranteeing enforceability. Interstate compacts exist because the states are sovereign. If there were no Compacts Clause in the U.S. Constitution, a state would have no way to enter into a legally binding contract with another state. The Compacts Clause, supported by the Impairments Clause, provides a way for a state to enter into a contract with other states and be assured of the enforceability of the obligations undertaken by its sister states. The enforceability of interstate compacts under the Impairments Clause is precisely the reason why sovereign states enter into interstate compacts. Without the Compacts Clause and the Impairments Clause, any contractual agreement among the states would be, in fact, no more than a handshake.

From 1932-2008 the combined popular vote for Presidential candidates added up to Democrats: 745,407,082 and Republican: 745,297,123 — a virtual tie.

The political reality is that the 11 largest states, with a majority of the U.S. population and electoral votes, rarely agree on any political question. In terms of recent presidential elections, the 11 largest states have included five “red states (Texas, Florida, Ohio, North Carolina, and Georgia) and six “blue” states (California, New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and New Jersey). The fact is that the big states are just about as closely divided as the rest of the country. For example, among the four largest states, the two largest Republican states (Texas and Florida) generated a total margin of 2.1 million votes for Bush, while the two largest Democratic states generated a total margin of 2.1 million votes for Kerry.

In the 25 smallest states in 2008, the Democratic and Republican popular vote was almost tied (9.9 million versus 9.8 million), as was the electoral vote (57 versus 58).

In 2012, 24 of the nation’s 27 smallest states received no attention at all from presidential campaigns after the conventions. They were ignored despite their supposed numerical advantage in the Electoral College. In fact, the 8.6 million eligible voters in Ohio received more campaign ads and campaign visits from the major party campaigns than the 42 million eligible voters in those 27 smallest states combined.

The 12 smallest states are totally ignored in presidential elections. These states are not ignored because they are small, but because they are not closely divided “battleground” states.

Now with state-by-state winner-take-all laws (not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, but later enacted by 48 states), presidential elections ignore 12 of the 13 lowest population states (3-4 electoral votes), that are non-competitive in presidential elections. 6 regularly vote Republican (AK, ID, MT, WY, ND, and SD), and 6 regularly vote Democratic (RI, DE, HI, VT, ME, and DC) in presidential elections.

Similarly, the 25 smallest states have been almost equally noncompetitive. They voted Republican or Democratic 12-13 in 2008 and 2012.

Voters in states, of all sizes, that are reliably red or blue don’t matter. Candidates ignore those states and the issues they care about most.

Being a constitutional republic does not mean we should not and cannot guarantee the election of the presidential candidate with the most popular votes. The candidate with the most votes wins in every other election in the country.

Guaranteeing the election of the presidential candidate with the most popular votes and the majority of Electoral College votes (as the National Popular Vote bill would) would not make us a pure democracy.

Pure democracy is a form of government in which people vote on all policy initiatives directly.

Popular election of the chief executive does not determine whether a government is a republic or democracy.

With the current state-by-state winner-take-all system of awarding electoral votes (not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, but later enacted by 48 states), it could only take winning a bare plurality of popular votes in only the 11 most populous states, containing 56% of the population of the United States, for a candidate to win the Presidency with less than 22% of the nation’s votes!

A presidential candidate could lose while winning 78%+ of the popular vote and 39 states.