.

.

.

Cross-posted from John Earl’s Surf City Voice, this is John’s father’s first-person account of a B-29 bombing mission over Nagasaki that he took part in as the flight engineer during WWII.

Keith “Blackie” Blackburn, flight engineer on another B-29; Tucker, the bombardier; Kit the navigator; “Pappy,” the pilot; E.J. Rush, Radio; Brennan, Radar; Bob Earl, flight engineer; Air Base Ground Crew Chief; Jack, co-pilot; Tews, Tail gunner; Mazzola, side gunner; Brzoska, side gunner; Krewson, top gunner. In Szechwen, China, Aug. 8, 1944.

Written by Robert W. Earl (1920 – 2015)

We climbed into the trucks to ride to the briefing room at 10:30 in the morning of August 10, 1944. The day was sunny and clear enough to see the Himalayas of western China rising 18,000 feet about 70 miles to the west. On the way to briefing, Kit, our navigator, and I argued whether they were real mountains or clouds. When we arrived at briefing many of the other B-29 flight crews were already entering the main room.

Pushing through the crowd inside the room, we looked for the benches marked for Captain “Pappy” Miller’s crew. The seating was arranged according to the rank of the pilot so we found our seats in the last row of the room. This troubled Pappy who had started looking for his seat in the very front of the room. After all, he had seniority in age and possibly hours. We watched him work his way toward us, his cigar drooping lower the closer he came to where we were.

I turned to Jack, our copilot. “Well, it’s a good start, Jack,” I said. “Pappy’s right in there pitching.”

“Hello boys. Everyone here?” Pappy asked.

“I guess so, Pappy,” I replied over the noise of the crowd.

“Whassat?”

“Yeah, Pappy. I think everyone’s in the crowd somewhere.”

Pappy turned to me. “I don’t like this raid.”

“You mean the incendiary bombing of civilians?”

“That’s what I mean. But I guess wah is wah,” Pappy replied in his soft southern accent.

“Well Pappy, they’d do the same to us if they had a chance. In fact, they’ve already done it to the Chinese many times.”

Colonel Bain stepped up on the platform and called the room to attention. “We’re going to bomb Nagasaki tonight with incendiaries. Our aiming point is the workers’ housing section to the east of the dockyards. We will take off at 16:30 this afternoon at 30 second intervals and bomb the primary target at midnight.

After the briefing ended we took the trucks back to the living area and ate a good lunch of fried chicken. Then the rest of our crew went back to the tents to rest until time to leave for the flight line. But I gathered my equipment and caught a ride to our B-29 parked in a hard stand at the airfield.

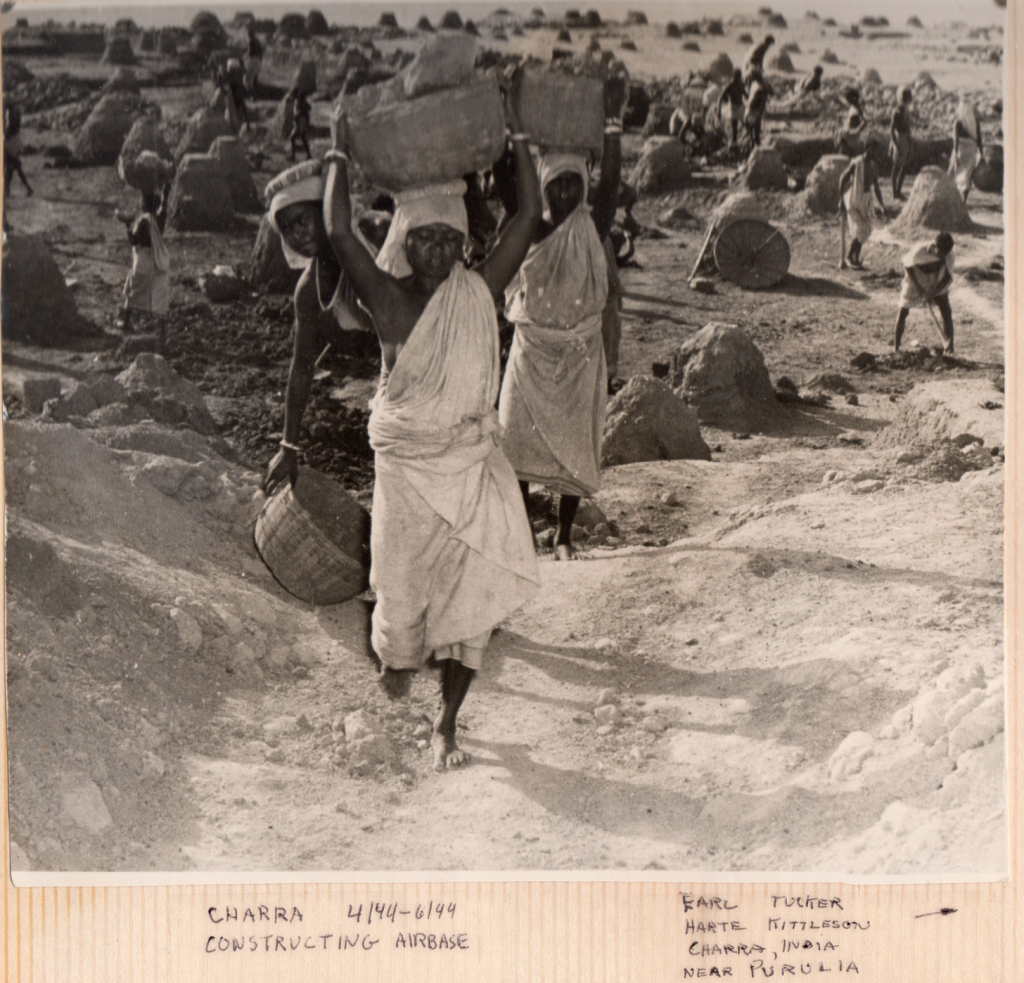

Thousands of Chinese men and women built this new airfield in the province of Szechwen, China, solely to serve the B-29s of our bombardment group of the 20th Air Force. Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese government had conscripted over 200,000 Chinese men and women to build the four separate B-29 airbases in the vicinity of Chengdu, China. And many of these Chinese were still at work on parts of the airfield weeks after we arrived in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater with our B-29s in April 1944.

This American airbase, under construction, was in India. Photo either by Robert Earl or U.S. Air Force

The 8800 foot runway, taxi strip, and hard stands were paved in naturally rounded, fist-sized stones carried in baskets to the airstrip from the banks of the adjoining river by individual workers. The workers first laid the stones by hand upon a base of sticky mud and sand. They then pressed the stones firmly into place beneath the weight of a ten-ton roller pulled and pushed by other hundreds of coolies. These four airfields amounted to man made miracles achieved in almost no time by the coordinated human endeavor of individual Chinese.

When I arrived at our hardstand on this pleasantly warm afternoon a crew from the airbase was guarding our B-29 Princess Eileen II (The first Eileen had crashed two months ago in a dry river bed in India with an engine fire). I asked the sergeant if all the last minute mechanical details were taken care of. He assured me, “Everything’s already to go, Lieutenant.”

In line with my crew responsibility as the flight engineer, I spent the next hour making a final check of the huge bomber and preparing my forms for the first mission our crew was about to fly against the Japanese home island of Kyushu. Several other crews in our squadron had already bombed the island twice. The first raid hit the steel mills at Yawata on June 15; the second bomber the naval base at Sasebo on July 7, 1944. So tonight, August 10, 1944, would be the third bombing raid against Japan proper since Doolittle bombed it from the carrier Hornet on April 18, 1942.

After completing my preparations, I visited the B-29 parked next to ours and joined my friend and roommate Blackie, another flight engineering officer, for a short walk to the banks of the nearby river. Once there we were tempted to try our strength against the weight of a pair of apparently unattended baskets of stones someone had left near the water. The two baskets were slung from ropes attached to both ends of a hardwood pole designed to be balanced on the worker’s shoulder.

So we each tried balancing the pole on our right shoulder while lifting the baskets off the ground. But the baskets were so heavy we were unable to budge them. Our complete failure at the task provoked friendly laughter from a Chinese worker, presumably the owner of the baskets, eating his lunch beneath the canopy of a sampan anchored in the river several yards off shore. We replied with equally friendly waves and smiles before returning to our B-29s to await the arrival of our crews.

At 3 pm, the trucks brought the crews out to the flight lines. Kit jumped off a truck while carrying his precious coffee without which he seemed unable to survive. Pappy walked up to me, “Is she all set, Bob?”

“As far as I can possibly tell, Pappy.”

“How are the bombs? Are they all fused?”

“I don’t know much about fuses, Pappy. Tucker will have to check that.”

“Yes, they’re all set, Pappy. Don’t worry,” Tucker, our bombardier, replied.

A photographer drove up in a jeep and wanted to take the crew’s picture. So we lined up in front of the airplane in our best hot pilot poses. Then Pappy had the photographer promise a print of the picture for each of us before he left.

For several minutes while awaiting the time to climb aboard a couple of us discussed the ethics involved in fire bombing Japanese civilians even if the Japanese army had behaved brutally toward Chines civilians at Nanjing and elsewhere.

Actually, fire bombing civilian populations for a strictly military purpose did not bother some of us as much as the present raid where any chance of a successful outcome actually furthering the war effort was unclear. More personally, there was also the thought that a successful raid against civilians would inspire less acceptance than hatred among the Japanese citizenry toward any airmen shot down and parachuted into their hands.

By contrast to our mission today from China, on this same evening, 58 other B-29s consisting of half of our own bombardment group, along with the three other B-29 bombardment groups that had accompanied us to the CBI theater, were scheduled to take of from a British airbase at China Bay near Trincomalee, Ceylon. From there they were to fly over 4,000 statute miles round trip across the Indian Ocean to bomb the Pladjoe Oil Refinery at Palembang, Sumatra. In the case of this raid, the enemy oil refineries were obviously self-validating military objectives. But due to the size of that mission to Palembang, our squadron was left with only seven B-29s to bomb Nagasaki…

READ THE REST OF THIS STIRRING TALE AT SURF CITY VOICE!

*Wonderful story…..thanks so much!

Thank you so much for writing this. My grandfather was Side gunner Stanley Brzoska. I never heard him talk much about his time in the air force. would love to share some more stuff he did save from the war. I do remember we donated the Yak coat the crew was given when the Princess Eileen II went down. The coat was sent to a air museum in Virginia or Ohio( i dot remember of the top of my head exactly but will check with my dad) as i understand it they were somewhere near the Tibetan boarder and were found by local missionary’s that were able to help them get back.